“Miss Blue! What are we going to do in the garden this afternoon?” asks a student at Escuela Manzo, an elementary school in Tucson’s largest school district.

“I don’t know. What should we do?” replies Blue Baldwin, the school’s Ecology Coordinator – the sole position of its kind in the city.

“Move the chickens?” suggests the first student.

“I know! We should clean again,” says another.

Yes, the kids think it’s cool to clean the garden.

“We teach the kids lots of different ways,” says Blue. “With some teachers, I have a standing classroom time, like for an hour once a week.” On Mondays, she works with kindergarteners and caters the lesson to what the teacher wants to cover. “If she wants to do a unit on cactus and a unit on chickens, I’ll come up with something that compliments that.”

Some teachers send their students out into the gardens in small groups to do farm chores, like cleaning, watering plants, weeding, moving the chickens, feeding the fish (there’s an aquaponics project in the small greenhouse), turning the compost and making sure it’s at the right temperature.

The school also offers an after school program through the 21st Century Community Learning Center grant, a federal grant that low-income and underperforming schools can apply for to have two hours of extra programming after school. “The first hour is academic support, like homework and tutoring, and the second is like the carrot at the end of the stick of fun, so the kids choose between karate and sports and ecology.”

But do kids actually choose to learn about worm composting over martial arts? I ask.

They do. “We have a rule here, nobody’s allowed to say ‘Ew,’” Blue says, laughing. “At Manzo, you say ‘Interesting.'”

A FOOD DESERT

Manzo is a predominantly Mexican-American school that’s part of a school district with 60,000 students. “This neighbourhood on the west side of Tucson is considered a food desert, because there are tons of convenience stores and fast food stores and liquor stores. And organic food is super expensive at the one Safeway.”

TAKING ROOT

The neighbourhood and school are, however, very culturally rooted and family-oriented, which helped Moses Thompson when he started the Ecology Program in 2006 – and a big part of what’s allowed Blue to keep it growing. “Kids who are here now, their grandparents went to this school,” says Blue. Thompson, the former school counselor, found that “when working with students in crisis, rather than reading books or doing puppet shows inside of an office, what was more effective was to actually get outside and do some work and move their bodies,” says Blue. “That’s when they would relax and open up and be able to process and communicate. And in doing that he began chipping away at different parts of the campus, just with the kids and their parents’ and grandparents’ donations for materials.”

Later, he started applying for small grants, eventually completely transforming the campus – starting with the desert tortoise sanctuary.

Once a tortoise is taken out of the wild, it’s not supposed to be reintroduced because of the potential of spreading disease, says Blue. “So you can adopt a tortoise as long as you have a habitat for it with the food and water that it needs.” The tortoise habitat that the school created is a piece of native Sonora desert, she explains, pointing to an area of cacti, shrubs, flowers and rocks surrounded by a short stone wall.

“In this neighbourhood, there’s not much native habitat. So I’m trying to bring the desert in, with its biodiversity. The desert’s amazing, because it’s an extreme climate and things surviving extreme climates are really interesting,” says Blue.

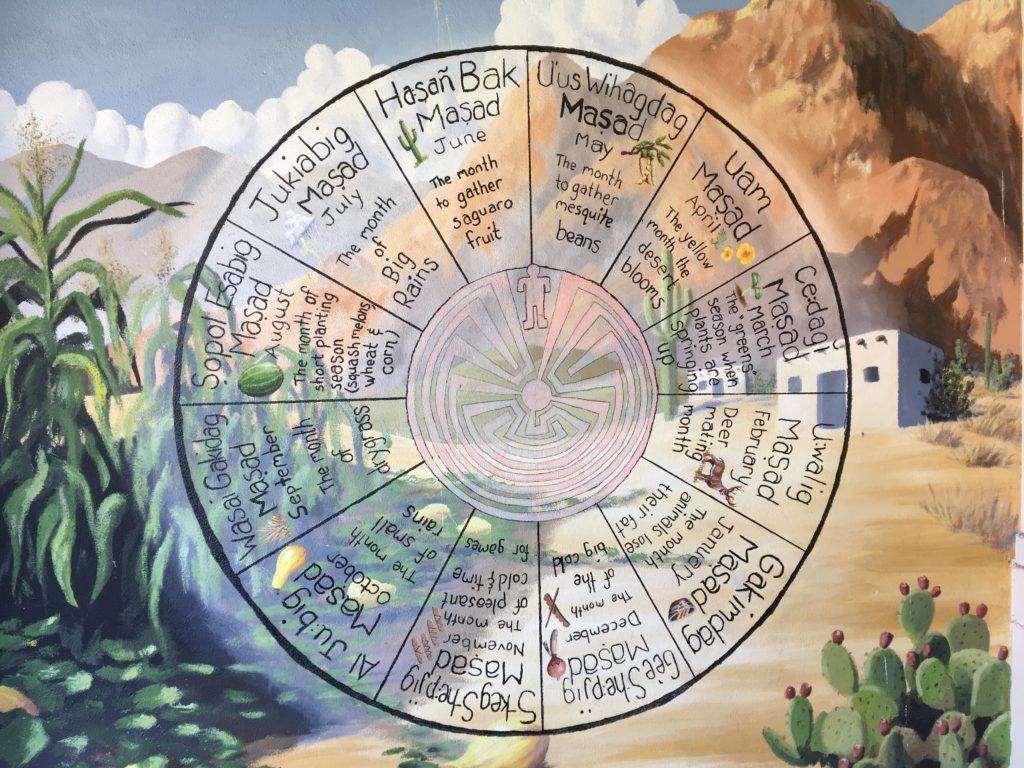

Another important part of the school’s desert heritage is its indigenous history. Painted onto the wall in the school’s inner courtyard is a mural by well-known local artist Joe Pagac. The circular agrarian calendar indicates the traditional Tohono O’odham changing of the seasons. The idea came from a couple students from the Native group, who painted the monthly planting and harvesting tasks along with weather patterns and their associated resting seasons and working seasons over Pagac’s background.

CARING FOR A SCHOOL’S URBAN GARDEN

In 2012, Escuela Manzo was awarded Best Green School by the U.S Green Building Council’s Center for Green Schools and in 2013 it was dubbed an environmental education success story by National Environmental Education Week. Thompson now works 50% for the University of Arizona and 50% for the school district, overseeing more than 30 other school gardens – but none with gardens and ecology program as elaborate as Manzo’s and none with someone who’s job is to ensure its continuance. “If there’s not a person whose job is to specifically to care for the gardens, it’s hard to maintain them. And then if it fails for whatever reason, like if a teacher moves on to a different school or it becomes too much work and nobody picks up the slack, or they don’t know how to garden, morale goes down the toilet. If it’s not done well, it can go badly,” says Blue.

The hens, rows of kale and chard, tomatoes, spinach, peas, fig, pomegranate and quince trees and happy tilapia are testimony to the fact that things are going well at Manzo. Blue has five undergraduate and graduate student interns this semester from the University of Arizona who come throughout the week to help. The community is still actively involved. Parents and neighbours buy the by-donation organic kale, chard, eggs and occasionally tilapia at the Manzo Markets. Some will also be helping out with the upcoming Fiesta Manzo, an annual fundraiser taking place today, Friday, April 6 at 5:30 p.m.

“At the Fiesta Manzo, each teacher has a little booth where they sell something, like a photo booth or snacks or concession stands. And we harvest tons of vegetables to sell and to give to this one mom who makes tamales and this giant pot of vegetable soup, which we also sell,” says Blue.

SUSTAINABLE SOLAR POWERED GARDENING

Next to a sports field outside of the school’s courtyard and classroom areas, giant solar panels shade rows of vegetables. Just out from under the panels are identical rows of the same crops – the control garden. These gardens are Manzo’s latest project: a collaboration with the University of Arizona to investigate the potential benefits of growing crops under solar panels.

“The solar panels are creating a microclimate by moderating heat,” says Blue. “In the winter, the sun’s shining on them all day. They’re made of metal, so they’re collecting all this heat that gets released throughout the night. We have summer crops under here that survived all winter, whereas out in the control garden, they died on the first frosty night. On the flip side, when it’s hot outside, the solar panels are creating shade, so they’re keeping it ten degrees [Fahrenheit] cooler than the control gardens. We seeded carrots in September, which is too early in Tucson because it’s too hot in September, but they germinated under the solar panels. In the control garden, we had to reseed and reseed and they didn’t germinate until November. We had cucumbers, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, basil – all this warm weather stuff survived all winter under the solar panels and did not out from under the panels.”

Now, they’re experimenting with exotics and using a monitoring system to ensure that the plants are getting enough red and blue light for photosynthesis. “We’ve got two mangoes and two avocado trees. And the avocados are looking amazing,” says Blue. “You only need so much light for plants to be happy and photosynthesize, and even under the panels, there’s plenty.”

Another advantage under the panels is that you don’t need as much water – which is important in the dry, desert soils of Tucson when you’re trying to grow tomatoes and other water- and nutrient-heavy plants.

FROM TRASH TO NATIVE HABITAT

As part of Manzo’s ecology program, kids take field trips to Tucson’s Mission Gardens to learn about native and historically important local trees and plants. Another – albeit closer – field trip is to the native garden habitat on a patch of land across the street from the solar panels.

“It was just an empty lot with couches and cars and trash,” says Blue. “So a teacher here contacted the city and asked if we could lease it and they were like sure. It’s like our walking field trip destination. Kids love going out there.”

FOOD SOVEREIGNTY ON THE MENU

Blue would like to see more of the garden’s harvest end up on the kids’ plates. “It’s actually a challenge because kale and chard, which is what we have a ton of, aren’t necessarily culturally appropriate. It’s an ongoing problem to get this stuff back into kid’s homes. That’s why we sell it by donation at the Manzo Markets.”

Could it show up in school lunches? “Something we can do is give it to the district’s food services department. They process it and the next day it shows up on these guy’s lunches as a salad or a smoothie,” says Blue, “but it’s not easy to do that. They don’t have the proper equipment.”

OPTIMISM AND WILLINGNESS TO CHANGE

The desire for change, however, is there. “The head of Food Services hired a farm-to-table chef, who designs a food literacy curriculum for students and helps get the garden produce into the school cafeterias,” says Blue. “Everybody believes in it. Everybody likes it. And change is happening little by little.”

As a student walks by, she high fives Miss Blue. I haven’t earned a high five yet, but Blue certainly has.

To learn more about Manzo Elementary and upcoming events, follow the school on Facebook. The Fiesta Manzo takes place today, Friday, April 6 at 5:30 p.m. at 855 N Melrose Ave.

Leave a Reply