I saw the hundreds of shooter glasses lined up on trays when I got the restaurant. the press event was just starting and servers were laying out the platters of creamy Portuguese cheese, baguette, silken and juicy Medjool dates and thick-cut fruit pâté.

So I figured there were shots coming. And I figured I’d politely decline. I know that distilled alcohol should officially be gluten free because the parts per million of gluten in it are so low – even if the distilled substance is made from wheat, rye or barley, like most whisky and vodka. But I’ve had enough bad reactions to be wary. I’m not talking overindulgence; I’m talking a few sips and I have a headache, don’t sleep well, have a rapid heartbeat and seem to get drunker and drunker.

But here I am with a crowd of proud Portuguese people celebrating the launch of the second season of a beautiful webseries and I’m being offered a glass shooter of something red.

“What is it?” I ask the server, who’s been pushing through the crowd all night and certainly has better things to do than answer an ignorant girl, I feel.

“It’s Portuguese,” he says.

“Yes, and what’s it made of?” I counter.

“Sour cherries,” he says, explaining that the speaker will present it later.

“What’s the base alcohol?” I knew I was going to get a funny look for that one.

“It’s just sour cherries.”

And there goes my trust. It’s clearly a hard liquor, and while fruit is happy enough to ferment on its own, it does not magically distill itself into high octane hooch.

Just take the shot, Amie, I think. It’s probably fine. A second server reads the Portuguese label and says the inly ingredient is sour cherries.

“It’s just fermented, like wine,” she says, saying a name I can’t understand, which I later Google and find to be “Ginjinha.”

I’m skeptical. But I take a sip at the appropriate toasting moment. It’s at least 40%, I’d wager. It’s not wine. It’s distilled, which means it must have a base alcohol. And it’s sweet, which means there’s been sugar added. (Think about what pure fermented wine would taste like if it were distilled without sugar – it would be extremely bitter and watery.) This could be a grape liqueur, like brandy, but it could also be cheap vodka or even high-proof alcohol that doesn’t warrant a name. A lot of your low-end, cheap cocktail ingredients are made with these, think Southern Comfort and lychee liqueur.

So I turn away from the woman and mutter under my breath: “You’re wrong.” Which I find highly satisfying. The liqueur is tasty and not a low-end product, but my anger comes from the woman not even knowing what the drink is. If it’s such a popular drink in Lisbon, you’re at a Portuguese event and you’re serving it to a crowd of people (one of whom will inevitably be an annoying person like me), you should know what it is.

To me, that’s like a Quebecer saying beer is distilled or wine is made with barley. Okay, maybe that’s too far, but it made me upset.

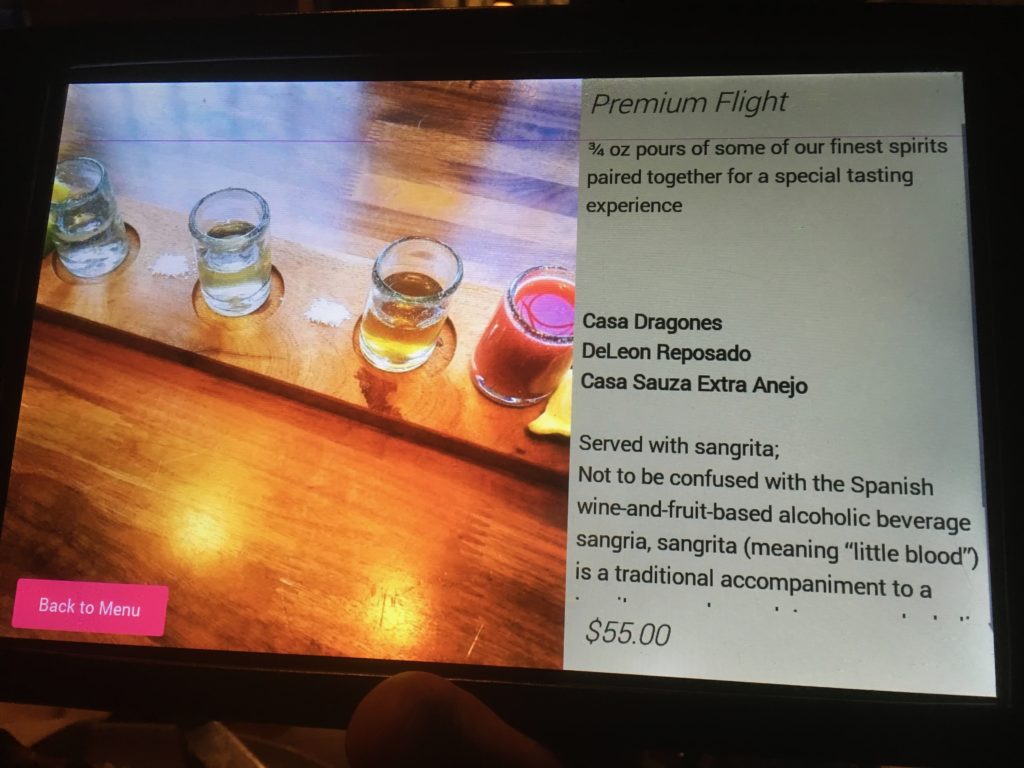

And it made me sad. Because someone from the Tequila region of Mexico would be pretty upset if you thought Tequila was made from wheat instead of agave. They’d probably get over it if you didn’t know it was specifically blue agave, but the point is there are limits to acceptable levels of cultural ignorance. Those are situational, sure, but when I was drinking Mezcal in Tucson, Arizona over Christmas, it was an important differentiation, Mezcal being made with any kind of agave, not just blue.

Someone from Japan would be pretty upset if you thought sake was made from grapes. And I’ve had enough high quality sake lately – and met enough incredibly proud Japanese people at Kampai Montreal – to know that’s not a mistake you want to make (though the Japanese would be incredibly polite about correcting you, or not correcting you).

For anyone with food and drink intolerances or patriotism, think of this as a shout of support. I too spend a lot of my time hunting down not just “safe” things to eat and drink, but delicious things.

And if you don’t know what you’re drinking, don’t feel as though you have to take the shot.

Leave a Reply